In his essay, curator and theorist Miloš Vojtěchovský reflects on the origins of The Kitchen, the ideas of its founders Steina and Woody Vasulka and their reflection in the programme. By introducing the personalities who were involved in The Kitchen, he outlines the diversity of the related artistic community. The article was published on March 12, 2021 in the art magazine Artalk.

I am a cybernetic guerilla fighting perceptual imperialism… VT is not TV. Video tape is TV flipped into itself… [Tape is metatheater…] Tape is feedback.

— Chloe Aaron, “The Video Underground,” Art in America May/June 1971

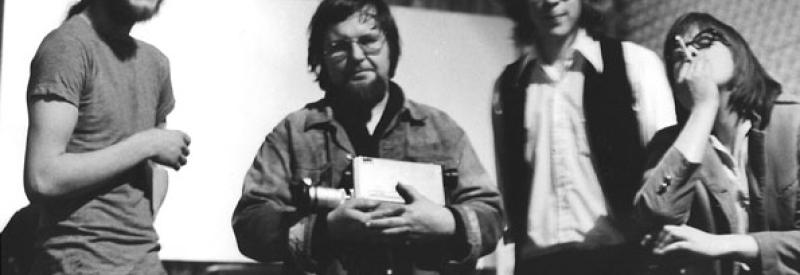

Almost 50 years ago, in June 1971, a trio of artists Andy Mannik, Woody and Steina Vasulka sent out an invitation to open a new space in the former Grand Hotel building on Mercer Street. They named the room and program The Electronic Kitchen, later referred to as the Kitchen. It came about during turbulent years, and the Kitchen was given an inspiring local context: on one of the two floors of the massive eight-story Mercer Art Center building, Richard Foreman had a studio with the Ontological-Hysterical Theatre; next door was the famed Oscar Wilde Room, a rock club where bands like the New York Dolls, David Johansen, Johnny Thunders, Sylvain Sylvain, Billy Murcia, and Arthur Kane Jr. performed and rehearsed. The surrounding streets were lined with art lofts, small restaurants, and independent theaters (Off-Off Broadway, as the non-commercial experimental scene is called here). The “Kitchen” could seat up to 200 people and the program ran 7 days a week.

The Vasulka’s reinforced their invitation with a somewhat “new age” manifesto: “This place was selected by Media God to perform an experiment on you, to challenge your brain and its perception. We will present you sounds and images which we call Electronic Image and Sound Compositions. They can resemble something you remember from dreams or pieces of nature, but never were real objects.”

If we were to compile a list of ten important places in the U.S. that have emerged over the last half-century out of the belief that culture and art signify revolt, free-thinking, experimentation, gender, class, sexuality, transnationality, and copyright openness, the Kitchen would probably not be absent from the list. But how do we distinguish the legend from the real story today?

Beginnings in the New York underground

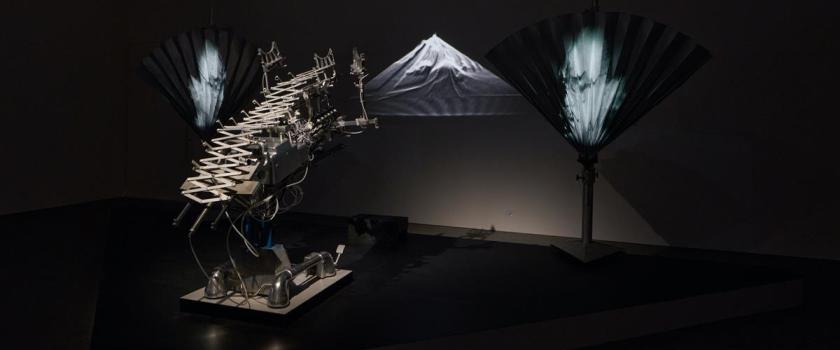

Throughout their artistic career, The Vasulkas have managed to create a creative aura and a diverse community around themselvees. The Kitchen, a kind of stage/theatre/laboratory, was their first and successful team project. Although in a different and much more professional form, The Kitchen still exists in New York today.

After arriving in New York in 1966, they found their feet relatively quickly in the local scene. From 1969 to 1971, Woody made a living doing various jobs, including making stuff for the porn industry. Thanks to a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, he also recorded rock concerts, theater shows, and “American Decadence” performances (the Participation series) at clubs like the Automation House, the WBAI Free Music Store, and Filmore East. He and his friends, who at the time included mainly the Swiss artist Alfons Schilling, attended parties at art lofts and clubs such as Global Village, Raindance, People’s Video Theater, Warhol’s Factory, and Jonas’s Cinemateque. At the time, Soho was still a cheap neighborhood near Broadway and the Lower East Side, and renting a space and organizing concerts, alternative galleries, and clubs was relatively affordable. In the same year as the Kitchen, Gordon Matta-Clark and Caroline Goodden were running the iconic Eat/Food restaurant on the corner of Prince and Wooster Street. Flux member George Maciunas had been in Soho since 1965 with his business and arts property acquisition project The Fluxhouse Cooperatives. Together with compatriot Jonas Mekas, and with the support of city grants and patrons Jerome Hill and Allan Masur, they were able to convert twenty houses into lofts for artists and art centers. A space for independent film, the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque, was created on Wooster Street as a precursor to the more famous Anthology Film Archives. Nearby in Cannal Street, another space with a similar dramaturgy to The Kitchen was already under construction in 1968. Under the direction of Phil Niblock, it still exists today, and even still in the same location: the Experimental Intermedia.

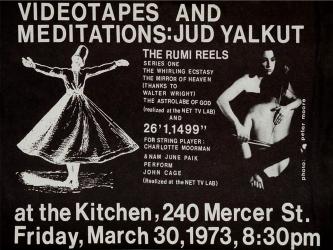

When the Kitchen opened, video and the Porta-pack camera were far from new on the New York scene, and it is therefore not entirely accurate to describe Woody and Stein as “pioneers” of the new medium. Video and audio had been experimented with frequently and wildly since 1967 or 1968, albeit outside most gallery and museum contexts. The first truly pioneering event in the field of “new media art” - 9 Evenings - was already realized in the autumn of 1966 by Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver under the label of E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology). Invited by the Boston television studio WGBH-TV in 1968, Nam June Paik began constructing his “television” sculptures and installations, and later collaborated on The Medium is the Medium, Fred Barzyk’s famous series of interviews with video artists for local cable television. In the spring of 1969, Ralph Hocking founded the Experimental Television Center laboratory and studio at Binghamton University north of New York City, Howard Wise opened a major exhibition on TV as a creative medium, and Beryl Korot and Phyllis Gershuny sent the first issue of the cult magazine Radical Software to the printer in June 1970, Willoughby Sharp filmed the first volume of the Videoviews series of interviews with Bruce Nauman, and since 1969, celebrated film director Shirley Clarke and the Tee Pee Video Space Troupe at the Chelsea Hotel have been experimenting with closed circuits, video sound, music and improvised dance. Groups of artists using video cameras, video collectives, and citizen cable television studios were active all over the U.S., especially in Chicago and, of course, major West Coast cities, and Paik dreamed of a new emerging America as “Videoland.”

For whatever reason, the Vasulkas were not invited to participate in the prestigious exhibition at the Howard Wise Gallery, and one can speculate that this may have contributed to the idea of establishing their own space for cultivating and presenting the art of video. Woody and Stein’s intention was mainly to encourage dialogue, encounters and exchanges between artists who saw video as a tool for live performance, or who wanted to create a base in New York for the development of new tools. A similar place was probably missing here, and the Kitchen program was a success.

The Vasulka’s and their colleagues took care of the operation and dramaturgy until the summer of 1973. Then, at the invitation of Gerad O’Grady, they went to the School of Media Arts at the University at Buffalo in upstate New York. By a strange coincidence, part of the former Grand Hotel building on Broadway collapsed in August of that year, killing four people in the rubble, and The Kitchen moved a short distance away.

Anals of the Kitchen

Approximately ten years later, Woody and Stein were living in New Mexico in their own home and didn’t have to move from place to place. They began organizing their voluminous archives and, with the support of Canada’s Daniel Langlois Foundation, moved forward with digitizing the documents. They then gradually posted hundreds, actually thousands of documents on vasulka.org: videotapes, photographs, diagrams, sketches for individual works, technical papers, grant applications, bills, correspondence, invitations, posters, pdf catalogues of their own and other artists they had worked with over the years. Woody and Stein comment on the archives in several interviews: they marvel at how casually some artists have handled the documentation of their own work. Thanks to their care, photographs, posters, interviews, newspaper articles, requests for support, and correspondence with patrons have been digitally preserved from the period of the Vasulka chapter of The Kitchen.

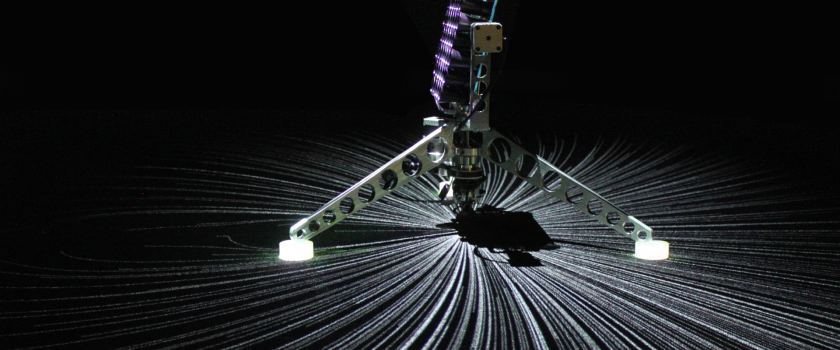

From the archives, we learn that a production and dramaturgical team quickly developed around The Kitchen: the composer Rhys Chatham was in charge of the music, and he opened the program with a concert by LaMonte Young. Dimitri Devyatkin, a video artist and producer, was in charge of the multimedia programme and festivals, the technical side of things was mainly handled by Shridhar Bapat, the concerts with video projections were handled by composer Michael Tschudin and Andy Mannik perhaps the dance. How the whole project unfolded over time is indicated by, among other things, an interview from 1973, of which an audio recording and transcript survives at vasulka.org: An Image and Sound Laboratory: A Rap with Woody and Stein Vasulka, Shridhar Bapat and Dimitri Devyatkin, broadcast by WBAI FM community radio. Towards the end, Woody (famous for his penchant for theorizing) defines himself against the simplistic conception of video as an artifact or as a mere activist tool. In his conception, video is not simply an extension of the television image, or a transformation of an analog film field into an electromagnetic signal and digital code. He agrees with the other interviewees on a critical view of contemporary video art, most likely aimed at the creators of videos and video sculptures that are intended for collectors and gallerists (somewhat disparagingly called “conceptualists”). Vasulka sees video as a machine for recording reality, but mainly as a transformative medium, changing not only established ideas about reality, but in fact reality itself, under certain conditions.

Video and power

Most of the East Coast artists were working within video collectives such as Raindance, Ant Farm, Radical Software, Guerilla Television, Videofreex, etc., and their techno-utopian vision was based on the belief that the video camera as a reproductive and distribution apparatus would change the cultural, social, and most importantly political order of American society by breaking the hegemony of the corporate or state mass media of television and radio, which would lose control over people’s thinking. But Woody saw video as an even more profound, if similarly utopian, means of transformation: as a result of the technological shift, the world of the future will be less “human,” a world where humans will no longer be the decision-makers, as we come to a consciousness of the usefulness of “fraternity,” of participation with synthetic, artifice-based thinking, or, if you will, with the “demons of the apparatus.”

WOODY: “What bothers me about the social use of video is the power struggle, which is quite reminiscent of other power struggles I’ve experienced. It was similar in Czechoslovakia: the first thing the Revolution did was to attach silencers to telegraph poles. Once there were tampers in the village and a functioning central microphone room, the problem of collectivization was a matter of two days. You could announce over the radio, “you’ll be there at five o’clock,” and people would come. I know the power of the media, if used politically it is incredibly powerful. The struggle for the media, even if it is, for example, public television channels, works on the same mechanism; it is a struggle for political power. Intuitively I am against such use, society must be flexible enough to resist political power; that is the basis of society....”

DIMITRI: “Talking about television, it is worth mentioning that about 80% of all half-inch video systems today are used for surveillance. Have you heard of state police departments buying huge quantities of cameras? They say they still can’t keep up with the equipment, but in any case, that’s the primary use of video technology.”

Woody was a firm believer in video and technology, though towards the end of his life he was somewhat skeptical about the potential of art to effect change in society. Rosalind Krauss, in her critical essay Video: The Aesthetic of Narcissism, published in 1976 in October magazine, judges that the “real medium” of video is primarily a psychological situation, a turning in on oneself, i.e. self-indulgence - narcissism. The artistic charge of video, unlike sculpture, painting or film, lacks weight, mass, physicality in its interpretation, which it substitutes with a disembodied, virtual image. Paradoxically, moreover, the very existence of the video image is dependent on an apparatus, external energy, an electrical or electronic device through which it is temporarily phantomized, “made present”. In Vasulka’s conception, this would mean, on the contrary, a positive: the irreplaceability of electronic images and the liberation from corporeality, the determination of the limits of human thinking and emotions. The truth is that for many tapes, or “closed circuit” video installations experimenting with the transmission of electronic signals, especially in the first decade - rather than images of the external world - it was the role of magic that was important, the fascination with grainy images of bodies, the shadowy faces of the author-cameramen. It was not necessarily narcissism, as Krauss denounces video art in a somewhat Lacanian and simplistic way. It could often have been an analytical approach, an introspection focused on the very structure of the electromagnetic image, or on the “meta-media” situation with which the electronic signal interferes socially or ideologically.

In a much later 2013 interview with David Plant (The Real Thing: An Interview with Rosalind E. Krauss), Krauss explains why she finds video as an artistic medium uninteresting. She compares video art to the sophisticated formal and content constructions of American (Canadian) structural filmmakers Hollis Frampton, Michael Snow, Paul Sharits, and the work of William Kentridge. Indeed, the work of the artists the Vasulka’s joined around 1970, and with whom they formed various temporary syndicates and alliances, did not seem deep, sophisticated, or attractive enough in the eyes of academic theorists, art historians, or film theorists, and most gallerists. But the Vasulkas didn’t really try to do that. Rather than being in the orbit of the gallery world, they felt more at ease in the company of all sorts of oddballs, inventors, rock musicians, mash-ups like Shridhar Bapat, Eric Siegel, Steve Rutt, Bill Etra, Ed Emshwiller, Alfons Schilling, as well as Nam June Paik, Tony Conrad, Jeffrey Schier, Joan La Barbara. Later in Santa Fe, for example, David Dunn, naturalist James Crutchfield, mathematician and mystic Ralph Abraham, and technologist and inventor Russ Gritzo. Outside of Nam June Paik and Conrad, few of these names have made it into major gallery spaces and “big” contemporary art histories.

When the Vasulkas handed over the management of The Kitchen to Robert Stearns in 1973, they entered into another temporary alliance: the Buffalo Heads. It consisted of James Blue, Tony Conrad, Hollis Frampton, Paul Sharits and Peter Weibel. At Buffalo, Woody and Stein finally had the opportunity and conditions to experience a well-equipped laboratory and contributed to the international reputation of the university, from which many later successful artists emerged. The Vasulkas remained in Buffalo until 1980, when they took the opportunity to move to New Mexico. In that climatically favorable and cultural landscape, they then contributed to another - their last - interdisciplinary project linking art, technology, and emotion: the Art and Science Laboratory, Techne and Eros.

Although they had a reputation in the international art community as formative and inspirational figures for several generations, Stein and Woody have long been rather overlooked by most American art historians and gallery curators. Perhaps because of their somewhat ambivalent stance toward the business and the “art world” in general, in a non-competitive model of the interplay between life, art, making, and cookery. In some ways, Vasulka’s position is perhaps comparable to that of another Czech-born emigre, the psychiatrist Stanislav Grof. Like Woody, Grof’s work is an important part of the cosmopolitan cultural map of the second half of the last century, even if his teachings have not been accepted by orthodox scholarship to this day. Czech filmmakers who attempted to succeed in the USA, such as Alexander Hackenschmied, Miloš Forman, Ivan Passer, Jan Němec, or Woody’s FAMU classmate Karel Vachek, either fought their way into the fortress of Hollywood (of which Woody was always critical) or gradually disappeared from the professional horizon in the USA. Vasulka, even as an immigrant from Eastern Europe, the owner of an Icelandic passport, without social security or health insurance, managed to carve out a space around himself for his existential and creative independence during his half-century career. Moreover - in a lifelong and complementary relationship with Steina, of course - they kept alive their idea of the media-lab as an open workshop of interdisciplinary incubator, a kind of creative hotbed in which unorthodox thinking and free art as liberated craft should be cultivated. It is no exaggeration to write that The Kitchen was their first collaborative and communal artistic fermenter, a petri dish and inspiration for myriad others.

The article is published with the kind permission of its author Miloš Vojtěchovský and the art magazine Artalk, where it was originally published.

The photographs are from not yet processed archive of Vasulka Kitchen Brno or the archive of Vasulka.org.

Miloš Vojtěchovský studied aesthetics at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University. Since the mid-1970s he has been active in the field of folk music and visual arts in Prague and elsewhere. Educational and professional activities. He lives and works in Prague.